Are Academics Cowards? The Grip of Grievance Studies and the Sunk Costs of Academic Pursuit

Posted on December 4, 2018 14 minute read by James A. Lindsay

There is much that should be said about the ways in which the dominant Social Justice ideology has negative impacts upon the university, free expression, academic freedom and, especially, the sciences. Like all rigid ideologies, Social Justice is inimical to science—not because of what it claims or concludes but because of how it goes about reaching its conclusions. Social Justice, like all rigid ideologies, is only interested in science that supports its predetermined theoretical conclusions and holds all other science suspect.

Of course, the accusation that the sciences are susceptible to the forces of Social Justice and its endless politicking may come as some surprise to those in the sciences, because they are duly confident in their own rigor. They are right to realize that, even if the Social Justice educational reformers go too far or have a frightening amount of institutional control, they cannot really influence science directly because they don’t do science. The assumption held by many, which is plausible, is that scientists will keep doing science according to rigorous scientific methodologies and needn’t worry much about the influence of politics from the more ideological sectors of the academy—including the administration.

This attitude is both laudable and quaintly naive. It is likely to underestimate the degree to which the sciences, like all disciplines, are susceptible to the influences and whims of a dominant orthodoxy. We should note that this exact concern is also what we hear from proponents of Social Justice when they attempt to encroach upon science—it’s perhaps the chorus of the siren song of feminist studies of science and technology to insist that the sciences are already biased and that their activism is a necessary corrective. These criticisms of science insist that science is already prejudiced towards the ideological assumptions of white, Western men and therefore needs to be made more inclusive. This argument, however, goes against the core and essential nature of science, which is universality. Whatever is true about the world should be discoverable by the same methods, regardless of who or what does the experiment.

Another core part of the scientific process is skepticism. This means that science, as a process, is already geared to minimize and correct for potential biases and errors, be they ideological or otherwise. Input into ways to do this more efficiently are always welcome, but Social Justice approaches do not seek to further improve the objectivity of science. Instead, they aim to introduce opposing biases, which they see as effectively counteracting existing ones. Far from being a novel or useful insight, however, concerns about the lack of objectivity on the part of any given observer or theoretician aren’t lost on any serious scientist or philosopher of science and haven’t been in decades (and appropriating Thomas Kuhn’s work here doesn’t work on the Social Justice side).

For these reasons, scientists should be deeply concerned with the possibility that people with strongly ideological and political motives, many of which are ambivalent at best and hostile at worst to the core values of scientific inquiry, might establish themselves as the body of working scientists and arbiters of what science can and should be done and for what reasons. Rigorous epistemology and a certain willingness to let the cards fall where they may and to have one’s ideas proven wrong will suffice.

The thing is, it is extremely likely that a majority of working scientists, at least outside of the social sciences, are keenly aware of the ways in which Social Justice can corrupt science, its conflict with the core values of science and science education, and its potential costs and implications. Nevertheless, it appears that they are letting it happen. Why would they do this?

There’s no real mystery in this question. Most of the scientists who see the writing on the wall and wish they could do something about it will eagerly tell you precisely why they don’t speak and act against the creeping woke hegemony they know will eventually corrupt their disciplines, possibly for generations. They’re afraid. They’re afraid they’ll be fired. They’re afraid they’ll be blacklisted from jobs, tenure and research funding opportunities. They’re afraid they’ll become thorns in the sides of the administration, especially the Grand Wizards of their institutions’ Offices of Diversity and Inclusion, and targets of the newly minted campus inquisition Bias Response Teams, and never have another peaceful day to get real work done. They’re afraid they’ll be done like Tim Hunt was done.

Outside of the academy, this attitude often gets them branded cowards. In fact, the insistence that academics are cowardly, and that’s how we got into this mess in the first place, is one that seems to have a worrying level of support lately. It’s probably true that significant numbers of academics are cowards. In the main, however, it is only true in the sense in which a person is a coward for knowing that the first few to speak out in a revolt against any hegemonic regime are going to be its first martyrs. Speaking game theoretically, she who speaks out first should always be somebody else.

On those grounds, it’s probably not correct to say that academics are cowards. We hear exhortations that they should have the courage to risk their positions by speaking out because they have options. They have PhDs for God’s sake—surely they can get another job somewhere. This is a popular myth, but the opposite is nearer to the truth. Getting a PhD often locks a person into very few options other than to toe whatever line is needed to stay in academia. If we’re going to solve many of the institutional problems facing the academic working environment, not least the creep of Social Justice ideology into these institutions, the reality of the PhD job market is going to have to be taken into account.

To understand and find a workable path forward, we need to empathize.

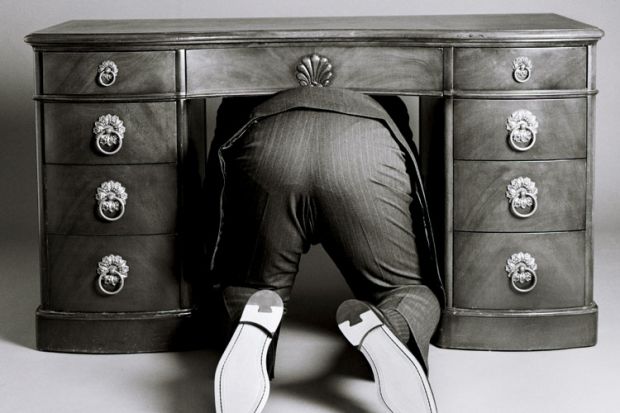

Imagine yourself as a relatively new PhD. Chances are that you have spent anywhere between the last three and twelve years dedicated to higher education, and you have been following a path of increasing difficulty, paired with increasingly specific and narrow focus. By definition, supposing your committee and institution were up to the task and you’re not a rather extreme outlier, you should be for about eighteen months the world’s foremost authority on some exceptionally narrow topic within a subfield of whatever field you tell people that you got your doctorate in. You’re going to be competent in other aspects of that field, of course, but it’s important to remember that you’ve spent at least the last two or three years of your program (or the entire program, depending on the country where you studied) going right to the bottom of some fairly deep rabbit hole.

Why did you do this? Passion. Love. Interest. Enthusiasm. To pursue the simple dream of doing something you genuinely love doing.

It’s virtually impossible to push yourself through a PhD program unless you truly love the subject you’re studying and want to devote your working life to researching it and teaching it—which means getting an academic job. And earning a PhD isn’t exactly a picnic. (When I did my master’s degree, my reaction was that it was a bit surprising how easy it was to earn compared to my expectations going into the program. When I finished my Ph.D., the only thing I could say was, “they don’t give those away!”) In nearly every case, it takes a great deal of dedication, interest and passion to earn a PhD, to say nothing of luck and talent.

The phrase grad student is misleading. It seems to many kind of like Easy Street. But many PhD students and postdocs work obscene hours—often in excess of eighty hours a week—to keep up with their educational, research and job duties, especially if they want to do well enough to score a tenure-track job later. They usually get summers off from coursework so that they can work even harder on their research, so there’s no real break there. They also usually do this out of passion and grit because there’s hardly any money in graduate assistantship stipends in the wide majority of fields.

And don’t get this wrong. This isn’t a poor PhD candidate story: it’s a tale of investment. A PhD program isn’t just school (or college); it is just another kind of apprenticeship like that any master tradesperson has to go through, except that it takes about a decade of insanely hard work to get through the first stage of it. To earn a PhD requires an enormous investment of time, energy, talent and resources. And what do you get in return (besides your degree and a set of wizard’s robes, complete with a hooded cape and a goofy hat)? (Note: You have to buy the robes and hat, and they’re expensive. Further, you’ll never wear them again unless you go into academia professionally.)

Pause to consider this. Chances are, if you’re looking for academic jobs, especially in the sciences, you’re coming off a postdoc or two, so you’ve literally spent the last decade or more in training for the job you hope to get. You’ve made incredible sacrifices for it. You’ve invested more into getting past the first hurdle of a future career than almost anyone else. Just imagine training at double full time, paid less than minimum wage, for a decade for a job and then being able to think it’s worth risking the career you’re working for to make a political point, even a really important or necessary one.

It’s not easy to call that cowardice when you see what it’s really about.

...